How to use human dimensions research methods to develop effective, future-proofed apps and online tools

Screen Escape, illustration by Jon Marshall

We have learned something important that our fellow conservation professionals should know: your customers (hunters, anglers, outdoor recreation enthusiasts, and others) don’t want another smartphone app.

If you are thinking about spending valuable staff time and budget on such things, stop right now . . . UNLESS you have determined what your customers fundamentally strive for — and what “jobs” they need done.

Online tools are proliferating and digital screen time has surged (to dangerous levels, some might say). These tools have tremendous potential for furthering conservation and R3 goals. But in our excitement to expand our digital dimensions, it’s critical to consider the fundamental “human dimensions” that should shape interfaces, schemas, algorithms, and data integrations. Digital innovation is not simply following what other agencies are adopting, or buying into the latest tech company product.

Digital innovation means making sure your agency’s investment is cost-effective and long-lasting. It means using a number of human dimensions, social science, and market research methodologies. It means placing high value on understanding a customer’s “job to be done.”

What is a "job to be done"?

A “job to be done” is a goal someone is trying to accomplish or problem they are trying to solve in a given situation.

We all have many jobs to be done in our lives. Some are big (find alternative funding for conservation efforts). Some are smaller (get funds approved for fisheries research project). Some surface unpredictably (respond to animal rights campaign); and some regularly (keep legislators and commissioners updated and informed).

In our personal lives, we also have jobs to be done. Some big (raise happy, successful kids and grandkids). Some small (weekend activities with kids/grandkids).

Hunters, anglers, outdoor enthusiasts — as well as teachers, landowners, private industry leaders, regulated constituencies, and others — have jobs to be done that apps, web/data services, and online applications can help achieve. Focus on jobs as your fundamental unit of analysis, and you’ll be well on your way to developing cost-effective, future-proofed, and truly useful apps and online tools.

From our experiences, here is what outdoor enthusiasts want:

- I want a stress-free hunt. I can relax and enjoy if I know I’m safe and legal.

- I want to know if I can keep the big fish I just caught and keep catching more (while they’re still biting). I don’t have time to read through complex regulations.

- I want to know what programs I might qualify for to help me improve habitat on my land whether they are state, federal, non-profit, or privately run programs.

- I want safe, fun, memorable outdoor experiences with my family.

- I want to support your agency’s efforts when you help me get my job done.

You’re fired!

When we buy or use a product*, we essentially hire it to help us do a job. If it does the job well, the next time we’re confronted with the same job, we will likely hire that product again. And if it does a poor job, we “fire” it and go in search of an alternative.

Every day, you hire people and things to help you do your jobs — both professional and personal. You count on others (your agency’s constituents) to “hire” your agency to get their jobs done. If you don’t provide viable “candidates” for them to consider, they will tend to go elsewhere.

Hiring and firing of solutions can be split-second decisions — or long-term considerations shaped subtly by personal and cultural identification. They can have powerful social and emotional dimensions.

A “job” is what someone seeks to accomplish, but this usually involves far more than just a single straightforward task. It’s important to consider the experience a person is trying to create.

Someone going fishing for the first time is trying to accomplish a far different “job” than someone who has grown up fishing her whole life. Digital experiences will have to differ to meet their different needs. The specific circumstances are far more important to consider than customer demographics, user characteristics, product attributes, new technologies, or trends.

* A “product” is any tool or solution that you might use to complete a job — large or small. It might be a device, a person, a location, a website, a service . . . or any combination of these things.

So what does this mean for websites, smartphone apps, and online data tools?

It means the success of your tech product (app, website, online tool, etc.) has a lot more to do with understanding “human dimensions” than it has to do with “digital” decisions like PHP versus C#, SQL versus Mongo, XML versus JSON, or . . . . . . sorry, geeked out for a second there.

It also means that there is far more involved in a successful product than designing an attractive, intuitive interface.

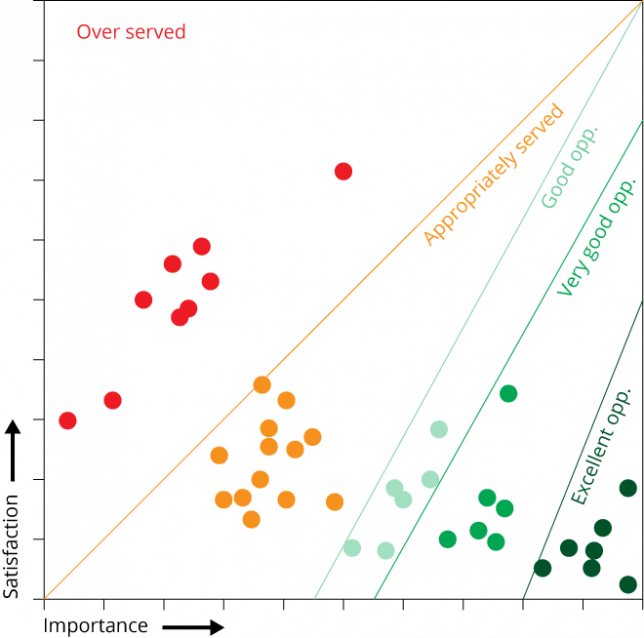

Opportunity map

Human-centered, outcome-driven research will reveal the areas of greatest opportunity for app and online tool development. Dots on this map are “jobs to be done” and are used to define and prioritize features, functionality, and technological approaches.

It means that you need to look through the lens of your customers’ (and/or prospective customers’) circumstances. You need to understand their jobs — big, small, and micro.

Once you have identified jobs, ask your customers to identify what are the most important jobs and jobs for which they have “candidates” currently available to complete them.

Inquiries like these will reveal an “opportunity map” to help guide where you spend your valuable tech product development time and budget.

A rigorous approach like this can take a little longer — but it need not cost more in the long run. In fact, your agency will likely realize cost savings in app development, operation, and staff management time costs over just a few years. You may find that some of the most expensive features your team envisioned are not your greatest opportunities and that there are other high priority opportunities that are relatively inexpensive to deliver.

Through such a process, you’ll also be armed with a discrete set of outcomes and specific measures/metrics to justify programs and sustain funding.

What to do now?

Our experience and research have shown us that hunters, anglers, and outdoor enthusiasts aren't looking for new apps to load on their phones. In fact, few people are. The "there's an app for that" fervor has subsided. People have become very selective about what apps fill their smartphone real estate. If you're trying to recruit hunters, promoting an app may even serve as a barrier rather than a gateway.

If your customers have a job for which a smartphone app is the best "candidate," then you should get it launched fast. But you should also consider emerging tools like "progressive web apps" and device-agnostic approaches. Consider "write once, publish everywhere" strategies to make your data and online tools FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable.

As a conservation innovator, you should embrace technology as a valuable, necessary tool. Just don't invest in apps for apps' sake.

Opinion/Preference Survey ≠ Human Dimensions

When considering tech product development, asking your customers what they want and what they like is not particularly helpful — nor does it likely lead to innovation. Preference surveys can potentially lead you in less-than-optimal directions.

Cool down now

Pursuing products and solutions based on their cool factor can lead to flash-in-the-pan products that don’t have the long-term staying power that makes your investment worthwhile.

P.S. We're always on the lookout for talented web application developers. If you have a public service heart, you're an experienced developer, and you enjoy collaborating for conservation, get in touch with me.

Follow up…

On the same day as this post (2/13/18), government innovation leader 18F published an article on a strikingly similar subject:

Why your agency (likely) doesn’t need a mobile app

The post covers reasons an agency might consider native mobile apps and when to pursue responsive web approaches.

February 13, 2018